Getting started¶

This guide will get you started with creating datasets for training and testing a deep learning based source separation model. Specifically, we will train a deep clustering network. There are five major steps:

Setting up dependencies

Setting all the environment variables

Creating the datasets

Setting up experiments (training and evaluating models)

Analyzing and reporting the results

This repository contains code that allows for quick and easy experimentation with the nussl library. With this code, you can easily experiment with the various hyperparameters that are native to each separation algorithm. The goal of this document is to guide you through setting up an environment via Anaconda and Docker, setting up experiment monitoring via comet.ml, setting up experiment reporting via a Google sheet, and training and testing your first model on a small dataset.

Just tell me what commands to run¶

Well first set up dependencies and environment variables below. Then…

make pipeline yml=data_prep/musdb/pipeline.yml

make experiment yml=experiments/music_dpcl.yml num_gpus=4 num_jobs=1

make pipeline yml=experiments/out/music_dpcl/pipeline.yml

make pipeline yml=data_prep/wsj/pipeline.yml

make experiment yml=experiments/speech_dpcl.yml num_gpus=4 num_jobs=1

make pipeline yml=experiments/out/speech_dpcl/pipeline.yml

You just created training, validation and evaluation datasets for music and for speech, trained 4 models on each domain, and evaluated them!

Setting up dependencies¶

You’ll need to first install Docker and Anaconda. If you want GPU support, you should install nvidia-docker and CUDA on the host machine. Once you have those two, you can start setting up the environment.

Setting up the conda environment¶

First, create and activate a Python 3 conda environment:

conda create -n [your_environment_name] python=3.7

conda activate [your_environment_name]

For some reason, it must be Python 3.7 due to a change in naming importlib in Python 3.8 breaking some dependencies. Then install poetry:

curl -sSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/sdispater/poetry/master/get-poetry.py | python

or by writing make poetry.

Then just run

make install.

This will install all of the requirements into the conda environment.

Setting up environment variables¶

The scripts are going to point to a lot of directories

(e.g. where your data lives, where to save experiment artifacts,

and so on). They may also depend on a bunch of API keys,

like access tokens for Google sheets (optional), API keys for experiment

tracking losses and logs on comet.ml (also optional). Each environment variable

is set in setup/environment/default.sh. First, copy default.sh to something

like [prefix]_local.sh. It’s important that the file ends in _local.sh. This is so that it doesn’t get tracked by Git! You’re putting sensitive API keys in there so be mindful!

Now edit your copied file [prefix]_local.sh. Below is a description of every environnment variable and how to set it.

The environment variables¶

These environment variables will be asked when you run the cookiecutter and replaced in the file automatically.

Required environment variables¶

export DOCKER_IMAGE_NAME="user/image"

This is the name of the Docker image that is used to run

all of the experiments. Usually it’s named with your name

before the / and some identifier after (e.g. your_name/your_project).

You can optionally add a tag afterwards, like

your_name/your_project:latest. The default is pseeth/nussl:latest.

If you don’t change this, it’ll just pull the image from DockerHub so you

don’t need to build it yourself. But if you add new requirements, you’ll

likely want to build your own image with your own image name.

export CACHE_DIRECTORY="/path/to/cache"

The training scripts generate a cache of input/output pairs for the network. These caches are zarr files that contain all the input/output for the network and can be substantial in size. It’s good to know where they are so you can free up hard drive space from time to time as needed.

export ARTIFACTS_DIRECTORY="/path/to/artifacts"

The experiment scripts all output their results in custom named folders whose names are randomly generated (by comet.ml). These folders get saved to /storage/artifacts/ inside the docker container. Good to know where these are so that you know where your results are.

export DATA_DIRECTORY="/path/to/data"

This folder is where all of your data lives for training and evaluating. This folder will be mapped to /storage/data/ in your docker container, allowing you to write the scripts in reference to those locations. Make sure you have read/write permissions for the folder you are pointing to.

export JUPYTER_HOST_PORT=8888

Jupyter notebooks run inside a Docker container as well. The port for the server inside the container (8888) must be forwarded to a port on the host. Select that port here (default is 8890). Find an open port otherwise it won’t work (this is for if you are sharing a machine).

export JUPYTER_PASSWORD_HASH="sha1:bed4d260d700:74cd5c1c5d43cab7e975a99c8bae5d6384d5891d"

You can set a password on the Jupyter server. By default, the password is password.

To change it, obtain the SHA hash for your chosen password. To do this, use:

from notebook.auth import passwd

passwd()

You’ll be asked to put in your password twice. The SHA value will display. Copy it (without the single quotes) and paste it below. This will be the password you use to login to the Jupyter server.

export TENSORBOARD_HOST_PORT=6006

Tensorboard can also run inside a Docker container. The port for the server inside the container (6006) must be forwarded to a port on the host. Select that port here (default is 8891). Find an open port otherwise it won’t work (this is for if you are sharing a machine).

Optional environment variables¶

export CODE_DIRECTORY=pwd

This tells the Docker container where the code containing all of

your scripts are. When the container starts, this is the folder you

will be in. You can assume relative paths from the root of this code

directory in your script. It now just uses the current working directory.

<!–

export NUSSL_DIRECTORY="/path/to/nussl"

This tells the Docker container where nussl is, so the scripts can import your version of nussl. This is useful if are editing nussl continuously and testing it. This is optional as you could just use the version of nussl on Github. But if you’re editing core nussl features, this is useful. –>

export PATH_TO_GOOGLE_CREDENTIALS=""

Experiment results are logged to a Google sheet. Put the path to the Google service account credentials here. Make sure that those credentials are not being tracked by Git. This only needs to be visible outside the Docker (not inside the container). For details, see the Google Sheets integration section.

export COMET_API_KEY=""

Put the API key you get from comet.ml after making an account here. comet.ml is used to monitor the experiments easily from anywhere as they run.

Google Sheets integration¶

SDR results are reported to a Google sheet for easy analysis at a glance. For more advanced analysis, you should use a Jupyter notebook or some Python scripts. To set this up, you’ll need a Google sheets API key as well as a copy of the template sheet in your Drive somewhere. Here is the link to the template:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1NwEjBAxFLuLWBd_KzyODvhgc9Y8hB7bnVZaWfzm_T40/edit?usp=sharing

Copy this to your drive, naming the document something that you’ll remember later.

Next, create Service Account Credentials via Google by following these instructions:

https://gspread.readthedocs.io/en/latest/oauth2.html. Once that’s done, you’ll get a JSON

file that you should save to somewhere. I put mine in private/key.json. Everything in

the private directory in this repository is not tracked by Git so it’s a safe place

to put it. The JSON file will look something like:

{

"private_key_id": "2cd … ba4",

"private_key": "-----BEGIN PRIVATE KEY-----\nNrDyLw … jINQh/9\n-----END PRIVATE KEY-----\n",

"client_email": "473000000000-yoursisdifferent@developer.gserviceaccount.com",

"client_id": "473 … hd.apps.googleusercontent.com",

"type": "service_account"

}

Go to the Google sheet you created above and share it to the email listed in the

client_email field in the JSON file above. This is super important!

Finally, fill out the field titled PATH_TO_GOOGLE_CREDENTIALS in the {prefix}_local.sh file you made above. You should now have automated access to

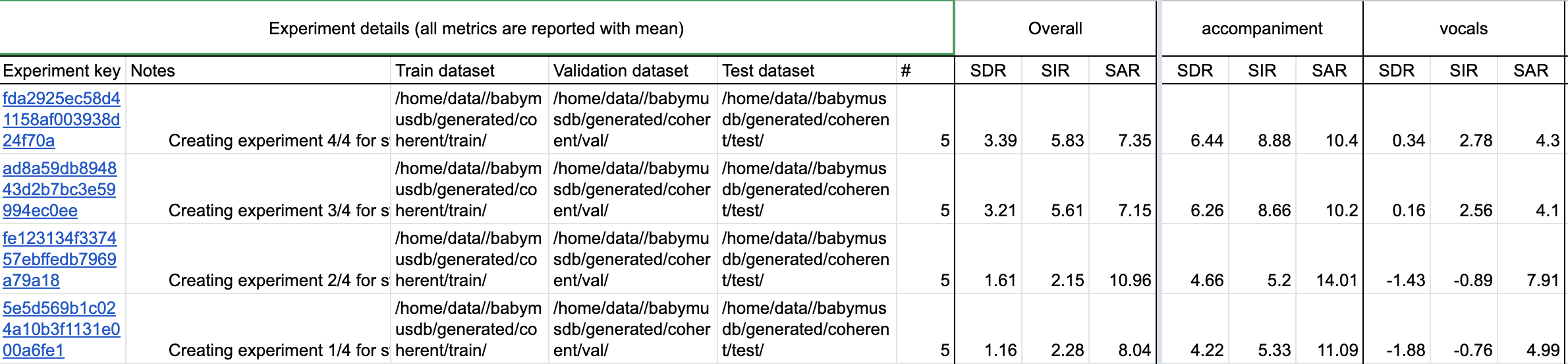

edit the Google sheet. The Google sheet will look something like

this after you do a training run.

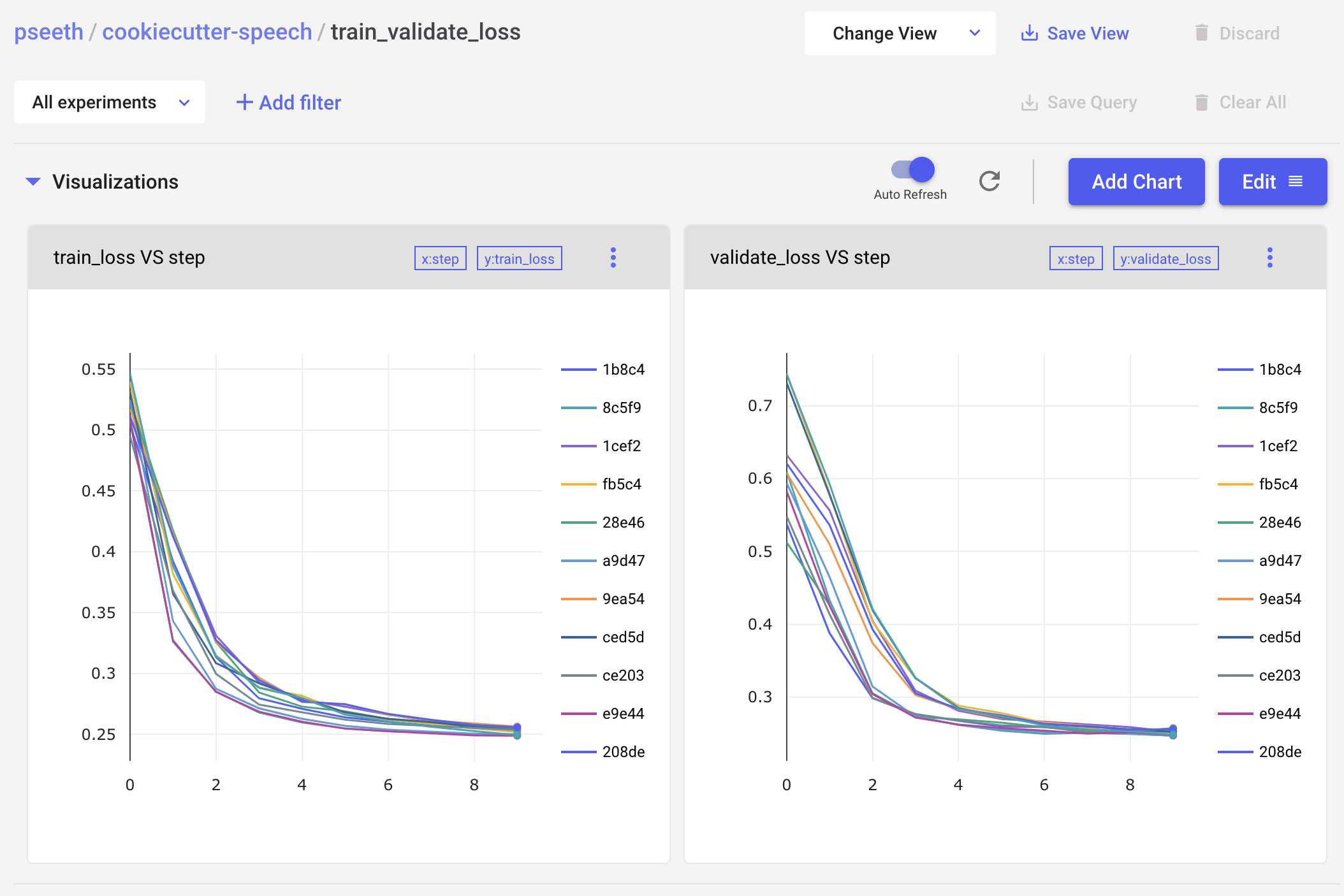

comet.ml integration¶

comet.ml is a useful way to keep track of experiments. It’s completely optional to use, just like the Google sheet, but it’s handy as it will make it easier to check your loss curves on the go and so on. You’ll get to compare runs like in the graphs above. The dashboard for a project looks like this.

Setting up Docker¶

Now, let’s set up Docker. If you’ve followed all the steps so far, this should just

require you to run make docker. Remember that if the docker image name and tag

are unchanged, it’ll just pull the image from the remote repository rather than

building it locally.

The Makefile¶

The Makefile will be your entrance to running all of the scripts. It has a bunch of useful commands. I’ll describe some of the more useful ones here, but the rest are detailed with comments in Makefile.

IMPORTANT

The most important thing before using the Makefile is to first source which enviroment setup file you are using. This needs to be done every time you shell in. So run this:

export ENV_FILE=setup/environment/{prefix}_local.sh

Replace the path with whatever or wherever the environment file you made is. After you do this, the Makefile can now be used. First, lets do some simple stuff to make sure the environment is set up correctly.

make check_environment

This will check the environment. Peruse the list to make sure your environment variables are set correctly.

Launching a Jupyter notebook¶

make jupyter gpus=0 name=jupyter-lab

This will launch a Jupyter notebook at the port specified in your sourced environment

file. Note that this make command takes arguments. The arguments are gpus and

name. The first controls the GPUs that are available to the notebook on the host

machine and name controls the Docker container name. The Jupyter notebook here

is run inside of Docker. The name of the container must be unique on the machine (this

can be a problem if you’re sharing the machine).

Launching TensorBoard¶

make tensorboard

You might want to run stuff in the background. To do that, just append

an &:

make tensorboard &

We now have everything we need to start creating datasets and training and evaluating models.

Pipelines and experiments¶

Two commands are special in the Makefile and are used for running pipelines (a sequence of jobs) and instantiating experiments (a specification that is used to train and test a model). These are:

make pipeline yml=path/to/yml

make experiment yml=path/to/yml num_gpus=4 num_jobs=1

num_gpus and num_jobs are special arguments to the script

scripts/sweep_experiment.py.

These will be described more indepth once we describe the scripting interface.

Scripts¶

All of the code you write should always be run via a script. Scripts in this

project take a special form for the purposes of reproducibility. Scripts always

taken in a YAML file which contains all the information needed to run the

script. For example, scripts/resample.py takes in a YAML file as follows:

jobs:

- input_path: ${DATA_DIRECTORY}/babymusdb/scaper/train

output_path: ${DATA_DIRECTORY}/babymusdb/scaper/train_16k

num_workers: 25

sample_rate: 16000

- input_path: ${DATA_DIRECTORY}/babymusdb/scaper/test

output_path: ${DATA_DIRECTORY}/babymusdb/scaper/test_16k

num_workers: 25

sample_rate: 16000

This YAML File is processed by the script to resample two datasets. A special

key called jobs can be used to run the script multiple times (once for each job).

The file above contains two jobs, one which resamples the train data and the other

which resamples the test data.

Note that there are special sequences like so ${DATA_DIRECTORY}. These, at run-time

will get replaced by the corresponding environment variable set previously. This

is so that scripts are portable between machines.

You must write a corresponding YAML file for each script that you write and execute. This is to reduce dependence on “magic terminal commands” that become undocumented and unmentioned as project complexity grows. Finally, reproducing an experiment then just becomes executing a sequence of YAML files.

Pipelines¶

There is a specific script at scripts/pipeline.py that is very useful.

The pipeline script allows you to run a sequence of other scripts using commands

from other scripts. A corresponding YAML file for the pipeline script looks

like this:

num_jobs: 2 # controls whether to run this sequentially or in parallel

jobs:

# Before doing anything, download the toy data the scripts below depend on.

- script: scripts/download_toy_data.py

config: data_prep/download_toy_data.yml

run_in: host

blocking: true

# First, reorganize the MUSDB dataset so that it can be fed into Scaper.

# Data should start off in a folder at DATA_DIRECTORY/musdb/raw/[train,test]/

# This is how musdb18.zip unzips.

- script: scripts/reorganize.py

config: data_prep/musdb/reorganize.yml

run_in: container

blocking: true

# Downsample each audio file from 44100 to 16000.

- script: scripts/resample.py

config: data_prep/musdb/resample.yml

run_in: container

blocking: true

# Mix a coherent dataset with Scaper.

- script: scripts/mix_with_scaper.py

config: data_prep/musdb/coherent.yml

run_in: host

# Mix an incoherent dataset with Scaper.

- script: scripts/mix_with_scaper.py

config: data_prep/musdb/incoherent.yml

run_in: container

There are a few things to note here. First, at the top of the script is how many

jobs to run in parallel in num_jobs. Then there is a list of jobs to be run in

jobs. Each item in the list can have five parameters:

script: what script to runconfig: what YAML file should be passed to the script for it to runrun_in: where to run the command, either on the host or the container.blocking: true or false, tells the pipeline to execute this script to completion before moving on to the next one. If not specified, it defaults to false.num_gpus: an int that says how many GPUs this script will need when run. Not used above but if it is specified, the pipeline script will execute the script with a GPU attached. If all GPUs are being used, then the pipeline script will wait until a GPU is free before executing the script.

So the script above will first download the toy data, then reorganize the data, then resample it to 16000 Hz. Then, it will the last two jobs in parallel - mixing the two datasets together using Scaper.

Try it now by doing make pipeline yml=data_prep/musdb/pipeline.yml.

Creating datasets¶

Now we’re ready to create datasets that can be used for source separation. To do this, we’ll be using a library called Scaper. But, we’ll be using my fork of Scaper which has additional unmerged features: my fork of Scaper. It was already installed via poetry.

Scaper expects your audio to be organized as follows:

root/

audio_class_one/

file0.wav

file1.wav

file2.wav

...

audio_class_two/

file0.wav

file1.wav

file2.wav

...

audio_class_three/

file0.wav

file1.wav

file2.wav

...

...

Preparing the data¶

First, you want to organize all your audio in the format above. Each class folder might be a different speaker, or a different sound class (e.g. car_horn, siren, and so on). After organizing the audio content for Scaper, you might want to first downsample all of your audio files to a different sample rate. Alternatively, you can let Scaper do this by setting the sample rate appropriately, but this will be a lot slower than just pre-processing.

Creating the Scaper dataset¶

Finally, the dataset is created using Scaper. The configuration of how the dataset is created is in data_prep/musdb/coherent.yml, along with a description.

All of these steps are done by the pipeline above. To run these steps on the toy data for music, do:

make pipeline yml=data_prep/musdb/pipeline.yml

To do it for music, do

make pipeline yml=data_prep/wsj/pipeline.yml

Creating experiments¶

Training runs are specified by experiment YAML files. There are two included in this repository:

See the comments at the top of music_dpcl.yml for a description

of how to configure an experiment. These YAML files contain every

possible thing you need to reproduce an experiment. Every single

variable, hyperparameter, data path, and so on, is kept in here.

For example, here’s what the train_config dictionary looks like

in music_dpcl.yml:

train_config:

class: Trainer

batch_size: 40

curriculum_learning:

- args: [400]

command: set_current_length

num_epoch: 0

data_parallel: true

device: cuda

initial_length: 400

learning_rate: 0.0002

learning_rate_decay: 0.5

loss_function:

- !!python/tuple

- dpcl # name of loss function

- embedding # what output of model to apply the loss function on

- 1.0 # weight given to the loss function

num_epochs: 10

num_workers: 20

optimizer: adam

patience: 5

sample_strategy: sequential

weight_decay: 0.0

Now, let’s say we wanted to try multiple experiments, with each one playing over

one of the variables above - like say, the learning rate and the sample strategy. To do that, you use a

special dictionary that can be defined called sweep as follows:

sweep:

- train_config.learning_rate: [.1, .01, .001, .0002]

train_config.sample_strategy: [sequential, random]

cache: '${CACHE_DIRECTORY}/musdb'

populate_cache: true # controls whether to create a separate experiment for caching

To instantiate an experiment you pass it to the script scripts/sweep_experiment.py.

This is best done via the Makefile:

make experiment yml=experiments/music_dpcl.yml num_gpus=4 num_jobs=1

This will create 8 experiments (1 for each item in the Cartesian product of all the

possible learning rates and the possible sampling strategies). Finally, you’ll

notice two special keys cache and populate_cache, that are not lists. To

understand what these do, you need to know a bit more about how training deep models

in nussl works.

Caching in nussl¶

A deep network is trained with input and output data. In audio, the input data is often

a spectrogram. In source separation, the output data is typically also spectrograms.

If you have a lot of audio files, computing the spectrograms of every mixture as well

as every source every time you want to construct a training example can be very

inefficient. This is because spectrogram computation can be costly. So, what nussl can do

is trade space efficiency for time efficiency by caching. So, if caching is enabled

(controlled by setting cache to be a string, rather than an empty string), then what

nussl will do is save all the input/output data to a file. This is done by zarr, which

applies compression to the files for space efficiency. zarr also decompresses in

a separate thread. This makes it highly efficient. The organization of a zarr cache

is similar to HDF5. Then, training the network is no longer limited by the computation

speed of constructing a batch. Data will come into the network as fast as it can

be read off of disk.

So in the above sweep, you set populate_cache: True, and controlled where to put

the cache via cache. What sweep_experiment does here is it creates a separate

cache “experiment” that only creates the cache. This experiment should be run

first before running all of the experiments (in this case the learning rate and sampling

strategy are tested).

Examining the resultant pipeline¶

sweep_experiment creates a pipeline that will do four things:

Populate the cache

Train each instantiated experiments. The number of experiments depends on the sweep configuration.

Evaluate each trained model.

Analyze the results of each model and upload the results to a Google sheet (if that is enabled)).

Here’s the pipeline constructed on my machine:

jobs:

- blocking: true

config: /home/pseetharaman/Dropbox/research/cookiecutter-nussl/nussl_testbed/experiments/out/music_dpcl/cache.yml

num_gpus: 0

run_in: host

script: scripts/pipeline.py

- blocking: true

config: /home/pseetharaman/Dropbox/research/cookiecutter-nussl/nussl_testbed/experiments/out/music_dpcl/train.yml

num_gpus: 0

run_in: host

script: scripts/pipeline.py

- blocking: true

config: /home/pseetharaman/Dropbox/research/cookiecutter-nussl/nussl_testbed/experiments/out/music_dpcl/evaluate.yml

num_gpus: 0

run_in: host

script: scripts/pipeline.py

- blocking: true

config: /home/pseetharaman/Dropbox/research/cookiecutter-nussl/nussl_testbed/experiments/out/music_dpcl/analyze.yml

num_gpus: 0

run_in: host

script: scripts/pipeline.py

num_jobs: 1

The pipeline is contained in experiments/out/music_dpcl/pipeline.yml.

Note that this is a pipeline of pipelines! The constructed training pipeline looks like this:

jobs:

- blocking: false

config: /home/pseetharaman/artifacts//cookiecutter/music/5e5d569b1c024a10b3f1131e000a6fe1/config.yml

num_gpus: 1

run_in: container

script: scripts/train.py

- blocking: false

config: /home/pseetharaman/artifacts//cookiecutter/music/fe123134f337457ebffedb7969a79a18/config.yml

num_gpus: 1

run_in: container

script: scripts/train.py

- blocking: false

config: /home/pseetharaman/artifacts//cookiecutter/music/ad8a59db894843d2b7bc3e59994ec0ee/config.yml

num_gpus: 1

run_in: container

script: scripts/train.py

- blocking: false

config: /home/pseetharaman/artifacts//cookiecutter/music/fda2925ec58d41158af003938d24f70a/config.yml

num_gpus: 1

run_in: container

script: scripts/train.py

num_jobs: 4

The random strings (e.g. fda2925ec58d41158af003938d24f70a) in there are created automatically by comet.ml. All artifacts from the training run will be kept in there. Run the

entire training, evaluation, analysis pipeline like this:

make pipeline yml=experiments/out/music_dpcl/pipeline.yml

This will do everything! To run just, say, the analysis pipeline do:

make pipeline yml=experiments/out/music_dpcl/analyze.yml

Or to load everything into a pandas DataFrame and do your analysis there, look at notebooks/analyze.ipynb.